Introduction to the Global Market Econ 101

There lies the field of flora, of all of Nature’s creation; the blossoms are the few ephemeral pleasures existing in the strangest of places: high on cliffs, hidden in caves, and cracks of concrete. As if to say that even in the most bizarre of crises, beauty can exist here. Laid out in rows of pink, orange, and yellow, assorted flowers greet me with only $15.99 per batch (or $9.99 through a membership). The morning, cold with rain, gently thuds on the hollow ceiling of Top’s Friendly Mart. Passing through the aisles, the shiniest apple reaches out, along with the matte of red tomatoes in film wrap, and the artificial dew of the fresh spinach rack. There’s a soft comfort in saving a few dollars, where fresh produce can be a luxury.

The LED lights, clunky carts, and automatic produce spirits are alien to what is natural. Nature boxed, shipped, and Saran-wrapped if she ever existed in this supermarket. William H. Albers coined the term “supermarket” in 1933, but the first supermarket was 17 years earlier, when Clarence Saunders opened the “Piggly Wiggly” in Memphis. For the first time ever, customers got to choose their personal selection of ingredients and assorted items. The aisle flooding with invisible violence as brands competed for this internal choice. But this makes me wonder why public markets aren’t as popular as the global south. From ancient Agora, Roman Forum, grand bazaar, and Tianguis, markets have existed for millennia, being as old as urbanity, if not the source of urbanization itself. The supermarkets weren’t first. Since the 1600s, public markets have been common all over Pilgrim-colonized Boston. Where farmers set out the day’s fruits, the butchers with fresh-harvest loin, bakers with the first breads, all the vegetables, milk, and trade gathered lively each with a role in one square. Instead, where multiple vendors, each a voice collectively gathering, a single company, a single building, a single brand, swapped the congregation for a conglomeration.

Although ostracized in the global north (the U.S., Canada, and 98% of Europe), markets in the global south have long been a thorn in Western notions of infrastructure. The public market, especially those of the third world, has informality characterized by resilience and perversion through self-appropriation of public typology. Twisting the parking, the mezzanine, or even underneath a highway, to a gathering of community members who simply cannot afford the luxury of a supermarket.

Countries that reside in the global south, with traits often outside the global political, economic, and cultural hegemonic system of today’s capitalism, are homes to markets that have long been an informal practice. Informality is best characterized not by what it has but what it lacks: clean edges, precise compositions, and intent. Best defined by Peter Mörtenböck & Helge Mooshammer in “Incorporating Informality”

Pop-up tents, folding tables, bag chairs, collapsible canopies, inflatable decorations, rolling carts, and container market stalls: a vast and increasingly complex array of flexible strategies has emerged to manifest the volatile and transient character of open-air marketplaces, even if these markets have achieved a sustained presence in the urban fabric over a longer period of time… sites of trade and commerce – that offer opportunities for economic growth.”

The two authors clarify this “mercado” informality through the lack of quality control, precariousness, and unequal power dynamics between tenants, all of which create a flexible crisis. The personality that allows for their organic resilience and creativity, surviving the drawback of a spatiotemporal permanent entity. Survival (always) the mother, being, and end of informality.

Often forgotten in today’s world of online consumerism, markets around the world are not mere corporations for the surgical precision of inventory distribution but a place where community, necessity entrepreneurship, and agriculture intersect. ตลาดสะพานเหล็ก [Talad Saphan Lek] was a historic Chinese market built on the abandoned Ong Ang canal of Bangkok’s Yaowarat district. Unlike other “ตลาด [talads]”, the market self-appropriated a capital infrastructure hanging precariously on shifting old wooden bridges over the royal body of water. With Chinese imported toys, electronics, and counterfeited goods, many locals and “pharang” foreigners alike often visited Saphan Lek for the affordable illicit items. Markets similar to Saphan Lek are morally gray, an intersection of outlawed practices and major economic income for the users of the gig economy, ebbing and flowing with under-the-table transactions lasting only weeks. They are the interstitial points essential for most lower-class urban living. Markets are not only places for daily groceries, but crucial during political uncertainty or economic recession, where few job opportunities lead to a rise in self-necessitated entrepreneurship. Street vending is not just a lowly profession but a survival and source of income for families. These informal infrastructures in the global south are not just “dirty” and “criminal” but pivotal nodes for a community without the financial means to shop or even work at big brand conglomerates. Eventually, these criminal ethnic and economic ties to China marked Saphan Lek as a red zone, resulting in years of subjugated government-mandated racism, targeted raids, evictions, and eventual closure.

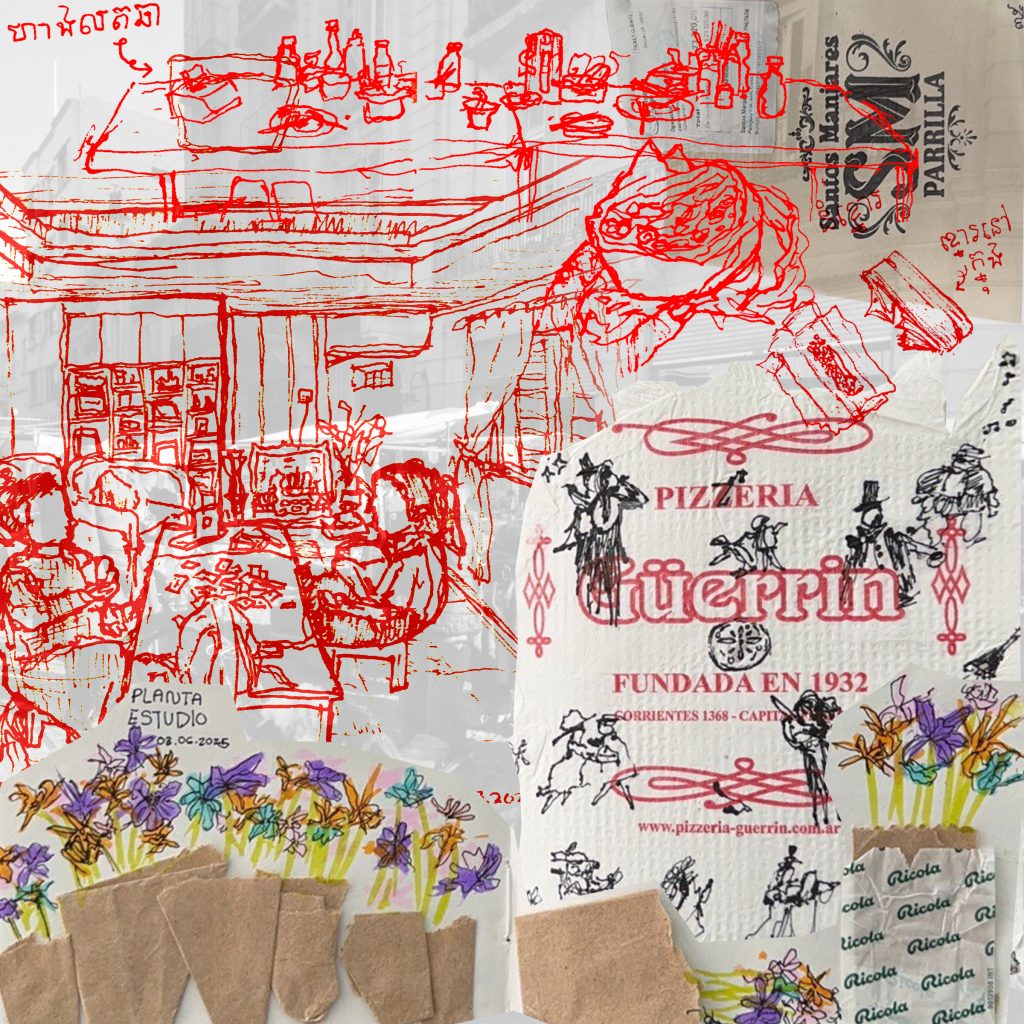

Unlike supermarkets, the acoustics of an open-air market are vibrant. The anti-corporational nature of street vending and informal bargains encourages neighborly dialogue, with the addition of the occasional yelling, of course. Although markets aren’t sanitized and earsplitting, with pavements often deformed, sometimes crowded, and always overstimulating, there’s a unique layer of humanity. Criminalized and imperfect, all markets have these traits to fall into the informal economy and blur boundaries. Buenos Aires’s La Salada fair faced a different criminal situation compared to Saphan Lek. The La Salada fair had distorted the Argentine economy and created a paraformal situation where the informal economy directly interacted with the formal in a way similar to laundering schemes. An informal economy, as coined in the 1970s by Keith Harth, describes a socioeconomic conduct that underreports and fails to be represented in the country’s GDP. La Salada, especially after the Argentine economic crisis of 2001, became a productive informal economy, providing not only locals but neighboring countries with affordable goods during a devastating recession. By 2003, there were an estimated 60,000 people passing through the markets with at least 400 buses daily arriving from Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Peru.

At its peak, the La Salada fair was the largest Latin American market with plans to distribute its model to Angola as part of a geopolitical vision for the South Atlantic basin. The success of La Salada fair had a key role from its trait as a locally informal practices profiting from commercializing cheap goods to a global formal economy that brought U.S. dollars to an Argentina with failing Pesos. Its downfall came from the criminalization of its practice as the government attempted to integrate it into a formal economy, combined with the global pandemic, the La Salada fair was indefinitely closed in 2023.

In the U.S, several contributing factors have led to the decline of public markets. The rise of supermarkets in the early 1900s, combined with the advent of the automobile, changed consumer tastes toward convenience. It’s easier to shop for groceries in one store than to be inconvenienced by multiple vendors while bargaining for scam prices. Markets slowly entropied as residents moved from urban centers to the suburbs. The invention of modern refrigeration and transportation further…for the urban nucleus to move from city centers to suburbs, from communal centers to decentralized aisles of home goods.

La Salada, Talad Saphan Lek, and every informal market were special in the way they provided low-income families with affordable daily meals, school children with snacks, self-employed vendors with income, and a communal center for the city. This desire for the informal isn’t a contained phenomenon but is reflected in the current entrepreneurial capitalistic venture appropriation and mimesis of the market aesthetic. Instances of which are seen in the Brooklyn flea company, Rod’s & Son Company’s Jodd Fairs, and Talad Rot Fai, with a jazzy mood, luxurious market, slow loss of clientele, and prohibitively priced Americano. Day by day, open-air markets where street vendors of all backgrounds, one selling greens, another live seafood, and others poultry, were the voices and gossip between customers and vendors dissolved. There is nothing super about the supermarket.

What draws me to these informal marketplaces is the rejection of mass industrial imperialism that is possible in meeting not only the consumer but vendors and the towns’ needs as a practice long before colonization. The informal approach is a quiet defiance to the common hegemonic system, financial market stock, market-rate housing, all these neoliberal terms in which man is born into. This formal imperialism is also reflected in the architecture pedagogy that has surrounded us, in the preference for productive formal gestures and overrated minimalism. Beauty can exist in the most ordinary places, not even grand or composed. The clutter and mess are unfairly seen, but it is the pure aesthetic of the ordinary folk, real and tangible. Our simultaneous fetishization and racial discrimination towards the informal and its economy not only blinds us to the workings of the entire global south, which, although deemed unproductive, in the end fuels the gig economy of the (W)orld we live in, which the global north exploits from.

Bibliography

- “Case Study: Saphan Lek.” Visual Culture, 27 July 2024, visualculture.tuwien.ac.at/en/blog/research-post/case-study-saphan-lek/.

- Jenkins, Dick, et al. “A Quick History of the Supermarket.” Groceteria.Com, www.groceteria.com/about/a-quick-history-of-the-supermarket/. Accessed 16 Nov. 2025.

- Mörtenböck, Peter, and Helge Mooshammer. In. Nai010 Publishers, 2023.