FROM DEGRADATION TO RENEWAL

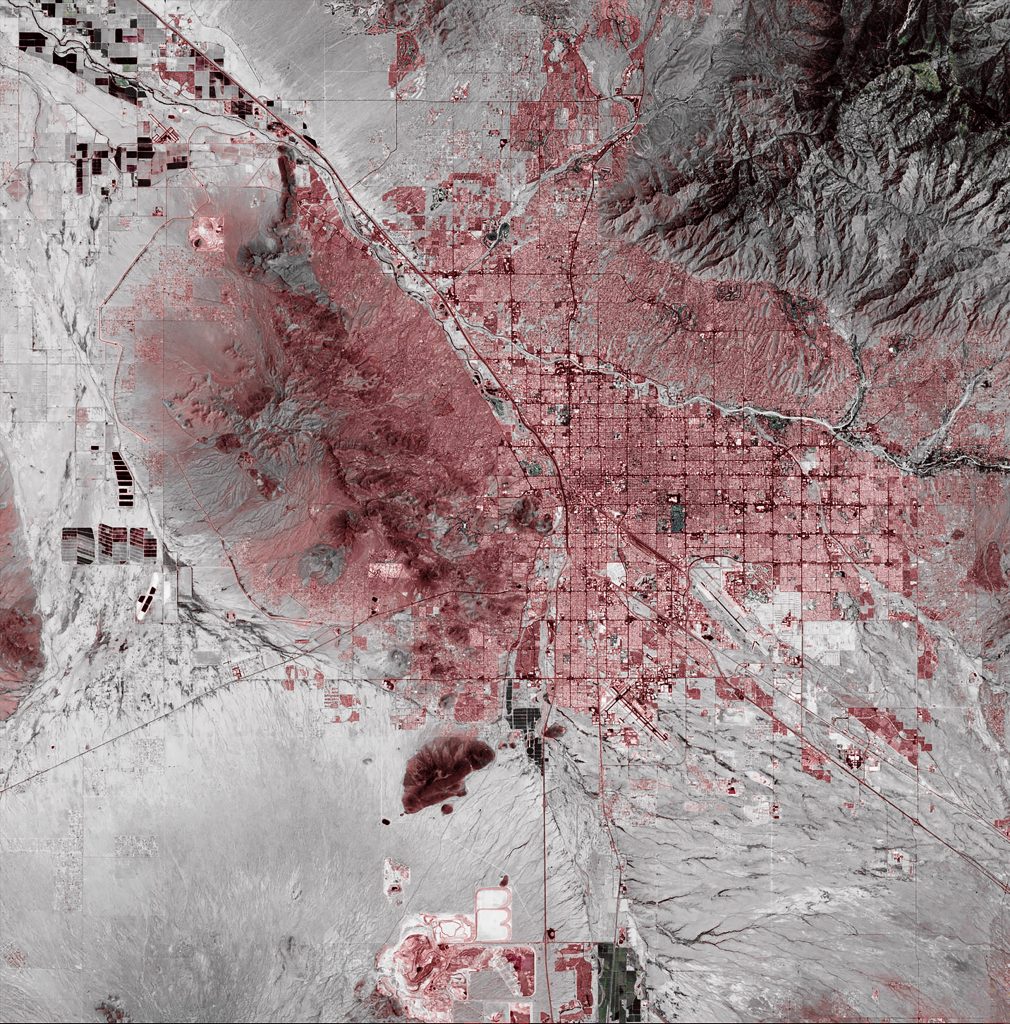

Once flowing continuously, teeming with diverse and complex life, the Santa Cruz River in Arizona is now dry and desolate, crushed by the human desire to expand and dominate. Prior to western expansion in what is now the Tucson area, the Santa Cruz River supported a wide and biodiverse ecosystem of flora and fauna. But as Tucson’s urban infrastructure and surrounding agricultural production grew, the river’s flows quickly faltered. In addition to the natural ecology, the river system was also vital to the livelihood of the multiple indigenous tribes, who depended on the seasonal flows for centuries before western intervention. The transformation of the Santa Cruz River from a perennial flow into a barren channel reveals a deeper cultural illness rooted in western societal ideals surrounding humanity’s relationship with nature. In modern society, built infrastructure behaves like a virus—appropriating, restructuring, and reshaping the very environments that sustain it. Despite this, restorative efforts can and should be undertaken, such as those undertaken recently with the Santa Cruz River, suggesting that infrastructure might also be reimagined as a regenerative agent, provided that we shift our design logic from consumption to restoration.

Infrastructure is often celebrated as civilization’s backbone: the network of pipes, canals, and highways that enable growth. Yet its logic is distinctly pathological. Like a virus, infrastructure invades healthy systems, hijacks their functions for human ends, and spreads relentlessly until the host collapses. Each new pipeline or aqueduct promises prosperity but often produces dependency, degradation, and loss. Nowhere is this clearer than in the American Southwest, where the ideology of mastery over nature has produced landscapes of extraction and exhaustion.

The Story of the Santa Cruz River is a small but powerful example of this viral expansion. For millennia, the river’s seasonal floods replenished groundwater and nourished mesquite bosques and cottonwood groves. The Hohokam and, later, the Tohono O’odham peoples built irrigation systems that echoed the river’s natural rhythms, diverting water gently without severing its ecological flow. Their relationship with the river was symbiotic rather than parasitic, a sustainable bond between water, soil, and community.

That balance collapsed with the arrival of modern industrial logic. By the early twentieth century, Tucson’s population and agriculture surged, and engineers viewed the river not as a living organism but as an untapped resource, waiting to be controlled. Groundwater pumping began on a massive scale. Wells drilled deeper each decade, pulling the aquifer farther from the surface, depriving the river of its baseflow. The Santa Cruz’s surface waters vanished, cottonwoods died, and riparian habitat withered. Simultaneously, agricultural irrigation canals siphoned what remained of natural flow, while flood-controlled concrete channels sterilized the river’s dynamic nature.

In a few decades, infrastructure accomplished what centuries of desert drought never could: it erased a river. The Santa Cruz, once a self-sustaining artery of the desert, became an engineered void, a corridor of dust where fish, frogs, and families once thrived. The consequences extended far beyond ecology. Indigenous communities whose cultural and spiritual practices depended on the river lost more than water; they lost the landscape that anchored their identity. What disappeared was not only a hydrological system but a social one.

The story of the Santa Cruz is not unique. Across the American West, and far beyond it, similar patterns have unfolded, each reflecting the same viral logic of extractive infrastructure. In Owens Valley, Los Angeles diverted the Owens River into its aqueduct system, exhausting Owens Lake and creating one of the largest sources of dust pollution in the United States. The Colorado River Delta, once a lush wetland teeming with wildlife, now rarely receives a drop of water, sacrificed to upstream metropolitan and agricultural use. On a global scale, the catastrophic collapse of the Aral Sea, one of the most dramatic human-caused environmental disasters, demonstrates the consequences of diverting river systems for industrial agriculture. These examples follow the same trajectory: extraction, followed by forced flow, followed by collapse. They reveal a cultural ideology that prioritizes mastery over nature, scale over restraint, and infrastructure as the ultimate symbol of progress. The virus is not only technological, but inherently philosophical and societal.

In recent years, however, the Santa Cruz River has become a site of ecological recovery and civic imagination. The Living River Project in Tucson introduced treated and purified reclaimed water back into the river channel. This reintroduction of flow, although artificial, has revived stretches of the Santa Cruz, restoring perennial water to areas that had been bone-dry for decades. Alongside this hydrological revival, new riparian forests have been planted, and community-driven restoration efforts have brought volunteers, ecologists, and local organizations into regular participation with the river. The local wildlife has bounced back, with dragonflies, herons, beavers, and migratory birds returning to many of the restored portions of the river.

This restoration reframes infrastructure not as a virus but as a potential healing network. Treated waste becomes lifeblood for an ecosystem in ruin. Floodplain reconnection becomes a circulatory repair. Riparian replanting becomes an act of ecological renewal rather than consumption. Challenges remain, including scaling up restoration, securing long-term funding, managing climate-related drought, and navigating upstream political pressures, yet the shift in mindset is palpable. The Santa Cruz River is no longer treated as a drainage ditch or flood threat; it is once again considered a living system worthy of care and remedy from past misuse.

Infrastructure has long spread across landscapes like a virus, invading ecosystems and hollowing them out. Yet the Santa Cruz River demonstrates that this pattern can be broken. It challenges us to rethink the fundamental role of infrastructure, not as a mechanism of consumption but as a platform for regeneration; not as an engine of expansion but as a tool for healing. The restoration of the Santa Cruz River reminds us that infrastructure doesn’t have to be a disease. It can become a remedy, if we choose to change the direction of its flow. In doing so, we learn that the built and natural worlds can, and must, coexist in a new rhythm: less domination, more partnership.

Citations:

AZPM. Making Arizona – Tohono O’odham Water. YouTube, uploaded by AZPM, 12 Apr. 2024, https://youtu.be/D7cKiZVv5E0. Accessed 16 Nov. 2025.

Sonoran Institute. “Santa Cruz River.” Sonoran Institute, https://sonoraninstitute.org/focus/santacruz/. Accessed 16 Nov. 2025.

Sonoran Institute. “Santa Cruz River: Paradise Lost, Paradise Reborn, Will It Be Lost Again?” Sonoran Institute, https://sonoraninstitute.org/card/santa-cruz-river-success/. Accessed 16 Nov. 2025.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. “Response to Flows in the Santa Cruz River.” U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, https://www.fws.gov/project/response-flows-santa-cruz-river. Accessed 16 Nov. 2025.